TAKE ZAIKU – THE ART OF JAPANESE BAMBOO CRAFT

Duration: December 2024 until December 2025

“Take Zaiku – The Art of Japanese Bamboo Craft“ is the title of the new exhibition at the IFICAH Museum of Asian Culture in Hollenstedt, inviting visitors to explore the intricate and time-honored tradition of Japanese bamboo craft. The subtitle, “The Art of Japanese Bamboo Craft,” provides a glimpse into the exhibition’s focus on this unique art form. Take Zaiku, meaning „bamboo craft“, refers to the skillful and delicate techniques used to transform bamboo into works of functional beauty, a tradition that has been passed down for centuries and continues to thrive as a symbol of Japanese artistry and innovation.

The term zaiku denotes craftsmanship that combines technical mastery with artistic expression, embodying the Japanese philosophy of dedication and harmony with nature. Bamboo, a material renowned for its strength, flexibility, and sustainability, plays a central role in Japanese culture, appearing in everything from architecture to tea ceremony implements. Over generations, artisans have perfected techniques that honor bamboo’s natural properties, turning it into baskets, containers, and decorative objects of timeless elegance.

The exhibition not only showcases the breathtaking results of this craft but also delves into the profound connection between material and maker. Each object reflects the artisan’s discipline, concentration, and commitment to perfection—a process that aligns with the concept of “dō”, the path to mastery. Visitors will have the opportunity to learn about traditional methods, tools, and the cultural significance of bamboo in Japanese daily life and spiritual practices.

As with all exhibitions at IFICAH, the challenge was to meet conservation requirements while providing a captivating and educational experience. Bamboo, while resilient, is sensitive to environmental factors, requiring careful attention in its presentation. The exhibition creates a space where visitors can appreciate the natural beauty of the material as well as the artistry and philosophy behind this ancient craft.

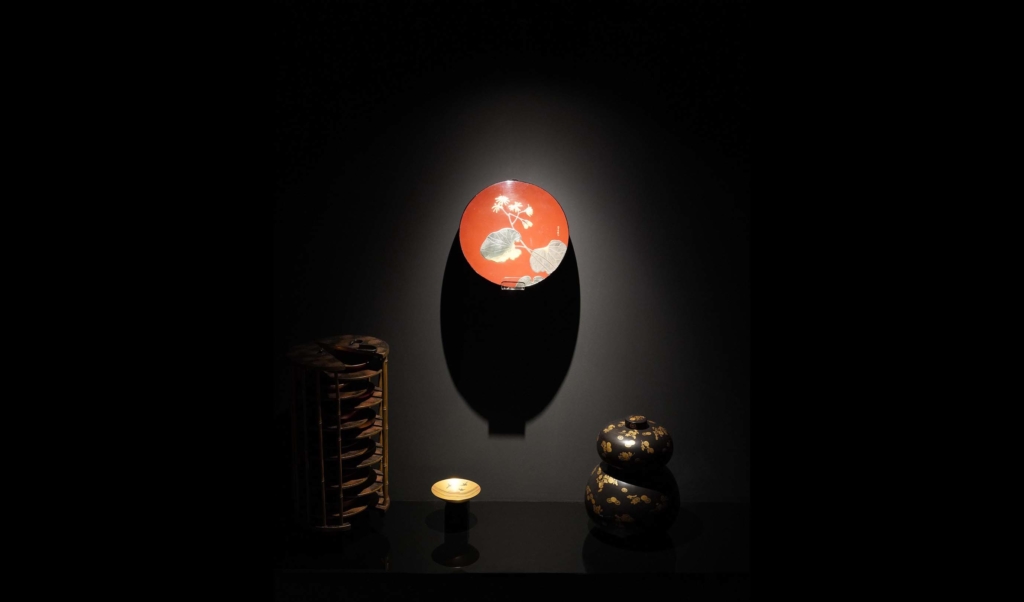

URUSHI-DŌ — THE FASCINATION OF JAPANESE LACQUER ART

Duration: May 2022 until September 2024

Urushi-Dō – the title of the new exhibition at the IFICAH Museum of Asian Culture initially raises the question of what it actually means. The subtitle „The Fascination of Japanese Lacquer Art“ may be of some help. Urushi, the lacquer of the Japanese lacquer tree, is a unique natural material whose processing has undergone virtually no modification for over 4000 years, and whose processing techniques have been declared a national cultural asset of Japan.

Many are familiar with terms from martial arts such as judō and kendō, or the term chadō from the tea ceremony. „Dō“ stands exclusively for something that can only be found in this form and consistency in the Japanese tradition: the path. The path that one takes with a clear goal in mind, a goal that one strives for, that one wants to achieve, but from which one moves further and further away the closer one seems to get to it. „Dō“, the Japanese path to mastery, means concentration, perseverance, dedication and an unlimited responsibility for what one does, a commitment not to oneself but to the task assigned to oneself or by a teacher.

The results of these techniques and demands are not only fascinating objects of art, they also captivate with their unique aesthetics. But these treasures are also very fragile, they react extremely to climatic influences such as light and humidity. The challenge of the exhibition concept was to implement the conservation requirements, the didactic introduction to the techniques and an aesthetic presentation that breaks completely new ground.

YOU CAN LEAVE YOUR HEAD ON – Asian Souls on Tour

Duration: April until December 2020

Life and death, the eternal cycle of evanescence as a basis for something new, is a taboo in many societies. However, there are ethnic groups to which death has been and still is a constant and natural part of life and their everyday life for generations. In its current project, the IFICAH Foundation is dedicated to six of these ethnic groups in Asia, from East India to Indonesia to the Philippines and Taiwan. Common to all groups is the association with the ethnicity of the so-called headhunters and therefore their direct and social bond of taking and giving. Often misrepresented by colonial powers and missionaries, the historical and cultural backgrounds of these ethnic groups were revised neutrally by IFICAH. In its Museum of Asian Culture, the results are presented to a broad audience based on the extensive presentation of previously unpublished objects.

Of course, you can still view our exhibition any time without an appointment. Use our new Digital Tour!

› Digital Tour through the exhibition

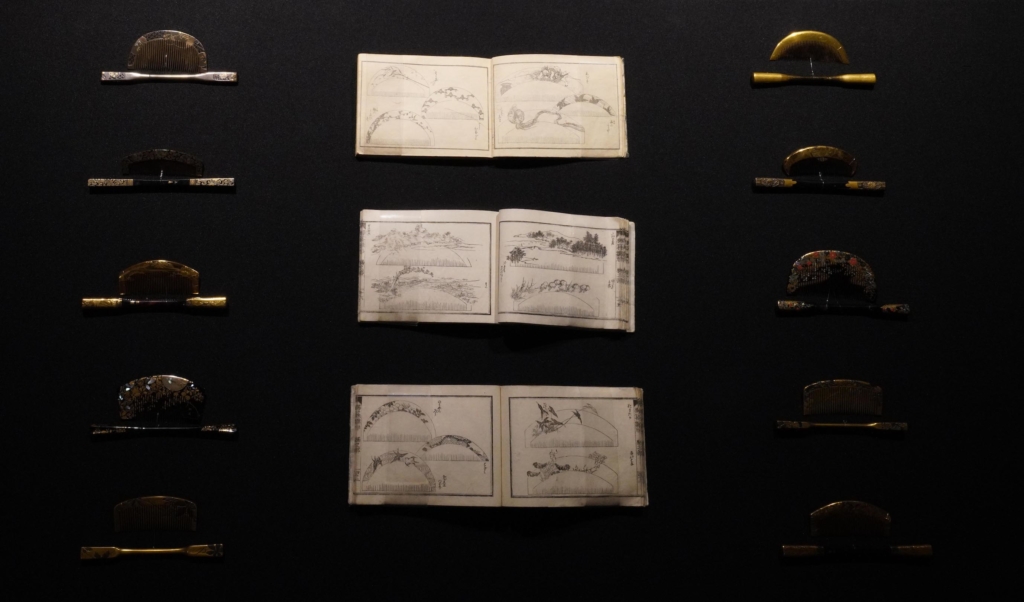

Noblesse Oblige – The Samurai and the fine arts of Japan

Duration: November 2018 – Setptember 2019

The Samurai. A social class of the historical Japan especially glorified by Hollywood. The IFICAH Foundation presents an exhibition in its Museum for Asian Culture, which will, based on the presented objects, show the Samurai from an unknown perspective for most of the visitors. The myth of the strong warrior is being extended with insights into the Japanese culture which would have not developed in these characteristics without the influence of the nobility at that time.

The clan watching over my shoulder

From February to October 2018, the IFICAH museum will introduce you to the ancestor cult and sword art of the Batak in North Sumatra. We have titled the exhibition „The clan watching over my shoulder“. Come in and impress yourself by the art of the Batak.

Joy of Silence – The aesthetics of the Japanese tea ceremony

Duration: until the end of september 2017

As early as the 4th century, Chinese Taoists were already using the leaves of the tea plant for the ceremonial preparation of beverages in their search for immortality. In the year 801, a Japanese monk brought tea seeds from China, which were then sown south of Kyoto. From the year 1191, Eisai the monk, who passed on the refined tea-making traditions of the Sung farm, was responsible for spreading throughout Japan the idea of refining the tea-making process by pulverizing the tea leaves. Initially, tea-drinking on farms and by the samurai was for the purposes of entertainment. In monasteries, thanks to its energising effect, green tea was used to stimulate the circulation during sustained meditation.

While in more elevated social circles tea was initially served in tea rooms, over time its preparation and serving became increasingly ritualised and moved to smaller spaces. This later gave rise to the detached teahouse, which usually formed part of the garden.

The further development of the tea ceremony culminated in the 16th century, when it was taken over by the tea master Sen no Rikyū (1521 -1591) in the so-called Way of Tea (chadō). The main objective of this Way is to carry out the ceremony in a quiet atmosphere as a type of contemplative art, surrounded by a reduction to elegant simplicity. Embedded in this idea is the goal of transforming life into a work of art through the philosophy of pared-down aesthetics. For Sen no Rikyū, the Way of Tea is based on the four basic principles of:

„wa”- harmony

Harmony is not only reflected in the design of the teahouse and tea garden, but also in the co-ordination of the tea-making implements, the attunement to the seasons, and last but not least the relationship between guest and host.

„kei” – reverence, respect

Respect and consideration determine both the behaviour of the participants in a tea ceremony towards each other, and their interaction with the tea-making implements and the environment.

„sei”- purity

Both the actual physical cleanliness and order of the teahouse and tea garden, as well as the symbolic cleansing of the guests and host, are intended to strengthen mindfulness and clean the participants’ hearts of the “dust of everyday life”.

„jaku“ – silence

The outer silence of the teahouse goes hand-inhand with the participants’ inner contemplation. In this atmosphere, the worries of everyday life fall away, and a mood of peace and serenity unfolds.

If these fundamental principles are applied to the Taoist Buddhist doctrine, “wa” stands for the connectedness of mankind and all living things in Buddhism, “kei” stands for the selfcontrol to respect all beings, “sei” represents the inner purity required to dive from the transient world into the world of tea, and “jaku” the solitary detachment, the immersion into nothingness as the dissolution of space and time.

Zen Buddhism provides tea masters with a framework within which they can unfold the Way of Tea and the associated aesthetics of imperfection and simplicity. By “entering” a tea room according to Sen no Rikyū’s requirements, each guest must move through the small opening which provides the only access. Regardless of social standing, everyone must subordinate themselves to the tea room. „Everyone who enters must bend their head, as if looking at their feet, and push the door aside. Just as all must leave their mother’s body, at the moment of entering the tea room, all must return to their true nature, like a new-born baby.” (Rikyū)

Despite the austerity and formality, the tea master gives the guests enough space to amuse themselves, and devote themselves to the details of the teahouse in silence and meditation. The charcoal ceremony precedes the actual tea ceremony. Water in a castiron kettle is heated over a hearth. Pieces of metal placed in the kettle add an acoustic element to the process. At the same time, incense is burned. The incense is taken from lacquer boxes and placed in special metal or ceramic incense containers. At the beginning of the actual tea ceremony, the tea bowl and the caddy containing the powdered tea are removed from their respective wooden box and cloth bag. The tea bowl is rinsed with hot water and dried with a cloth. Guests are served sweets to enhance the flavour of the powdered tea.

With a small teascoop, usually made of bamboo, the tea master takes some tea powder from the ceramic caddy and places it into the tea bowl. Water is taken from the kettle using a bamboo ladle and poured over the tea powder. A small bamboo whisk is used to whisk the tea until foam is formed in the middle of the bowl.

The tea is now served to the guests. The bowl is always turned before being given to a guest. There are many variations of the ritual for turning the tea bowl. In the Urasenke school of tea-making, as a form of homage the host offers the bowl to the guest with the most beautiful side of the bowl facing the guest. The guest then turns the bowl a little so as not to touch the most beautiful side of the bowl with their mouth. This shows the guests’ deference to their host, and their respect for the tea bowl. Finally, the bowl is cleaned and filled with a thinner tea, which in turn is served to the guests. The host or tea master does not drink tea, merely prepares it. After drinking their tea, guests talk amongst themselves in a relaxed mood before leaving the room.

The Gods & the Forge – Balinese Ceremonial Blades in a Cultural Context

Duration: Until mid november 2016

Summer 2015. Ketut, a native of Bali, picks me up on an ancient motorcycle. With our feet clad in nothing more resilient than sandals, we ride along streets barely worthy of the name to the hinterland. We meet people from different generations who live in impoverished conditions by western standards and who welcome the „giants from the West“ with typical Balinese warmth. Ketut introduces me to some of them, including his father. We drink very strong, sweet coffee and wait for the only person in the village with the right to open the holy shrine and handle the ritual objects stored therein. Together we go to a small hut and squeeze our way through a narrow passageway to a wooden door. The door opens and we proceed barefoot, entering a room lit only by a weak bulb. Everything is covered in a thick layer of dust. Cobwebs entwine the objects and paintings. There is a strong smell of incense, herbs, and soot. After a short ceremony, the shrine is opened. With great pride and deeply shining eyes, I am shown the broken, holy lance tip, which has protected the village and its inhabitants for many generations. A group of children and teenagers stand behind me, watching curiously as I record events with my camera.

When we are all sitting in the village square, Ketut explains to me that the objects from the shrine in the village where he lives with his family were sold because there was no longer anybody who could carry out the ceremonies, and because all the young people are leaving this rural area.

Years earlier, the fishermen had sold the land bordering the beach to Western estate agents, which meant however that they can now no longer access the sea with their boats …

It is precisely these experiences that underline the urgency of the work carried out by IFICAH – International Foundation of Indonesian Culture and Asian Heritage. At the beginning of the 21st century, the preservation of culture, social structures, objects, and traditions in many areas of the world – – even here in the „saturated West“ – is fading increasingly into the background. But these are exactly the structures that form a basis for a society with which future generations can also identify. Communicating with one another, showing mutual respect, or perhaps just drinking a far-too-sweet coffee together and smiling at each other: small intercultural encounters and small steps towards open co-operation on a global scale.

By presenting objects with accompanying texts, the exhibition „The Gods & the Forge – Balinese Ceremonial Blades in a Cultural Context“ represents one such step towards bringing an often unknown or forgotten culture and its handicraft skills to a wider audience.